Disneyland: The Eternal Happy Ending

A perfect utopian model that provides children and adults with a safety already heralded by the metaphysics we inherited from religions.

In order for paradise to be paradise we have to imagine it in our own terms. If we arrive to an unknown place full of strangers we will probably not feel the familiarity required to call it a paradise. Catholic “Heaven”, for instance, is populated by angels and divine figures that religious people have been taught to love through stories and representations, and is already part of their imagery of afections.

Walt Disney followed the same principle: he devoted his life to captivating the audience with his animated characters, and then built a paradise inhabited by them; an absolutely trust-worthy place where one recognizes everyone and everything, and feels welcomed by exactly what one expected to find.

In this sense, his model was impeccable. Disneyland provides children and adults with a safety that has already been heralded by the metaphysics we inherited from religions. Walt conceived and premeditated it as an Ouroboric utopia ––one that emerges and ends in a single stroke. Even physically, the first of these amusement parks was delimited by train tracks (operated by Mickey Mouse) which cut it off from the world and moved around the fantastic land like a snake biting its own tail. The brilliant Walt Disney relied on this ancient formula to create a paradise and to ensure it was a shelter removed from the world, as well as a vision shared by several generations. And it worked.

When the first Disneyland opened its doors in Anaheim, California, in 1955, Walt Disney devised the perfect design for a new type of amusement park ––one with a single entrance, hidden from nearby streets, with custom rides that put storytelling ahead of thrills. The more he imagined a “magical park”, the more imaginative and elaborate it became. The park was divided into five realms: the idyllic memory of Main Street, U.S.A, where he revived the traditional American turn of the century; exploration and the exotic in Adventureland, where he invited the audience to imagine themselves in remote places on Earth; Frontierland, to revive the pioneer days of the American frontier; Fantasyland, “to make dreams come true” and Tomorrowland, where the “wonders of the science of the future” were displayed.

He built wild animals as believable as he could, a Mississippi steamboat, the enormous castle of Sleeping Beauty, and many other prototypes and stereotypes of a fantastic American Dream. But stories remained his primacy.

In the Magic Kingdom one increasingly finds the magical atmosphere of his sugarcoated fairytales, the grumpy pirates that infect you with their songs, the story with the eternal happy ending —the metaphysics without tragedy. One can even find and hug Mickey, or take a picture with him; clear testimony of how that “reality apart” built by Disney does not have to be out of the viewer’s reach: it can be felt and held and be captured in pictures. A perfect and, of course, multimillionaire utopia.

Disneyland recreates everything we ever wanted to know without having to wait for death. It’s the most impressive and perfect production of an artificial paradise that does not hide its artificiality but, on the contrary, reiterates it over and over again so that the audience will feel comfortable in the “make believe” ––so that, with maximum naturalness, it includes the plastic characters and fairytales in its mundane metaphysics. The televised dream becomes real in this kingdom, where our imaginary friends await us and the happy ending is never an ending —there is no tragedy—; it’s the never-ending story.

Related Articles

When ancient rituals became religion

The emergence of religions irreversibly changed the history of humanity. It’s therefore essential to ask when and how did ancient peoples’ rituals become organized systems of thought, each with their

Larung Gar, the valley that is home to thousands of Buddhist monks

If we think about the monastic life it is very probable that we think about solitude, seclusion, silence and a few other qualities whose common denominator is the appropriate isolation for mediation

Dialogue with the Dalai Lama on science and spirituality

The Dalai Lama has been interested in science since he was a child. Over the years he’s visited many laboratories and has attended conferences that discuss consciousness from the scientific point of

A New Year's resolution for the earth

Worrisome quantities of waste are generated by human populations. Especially in cities, these have reached unprecedented and alarming levels. A largely uncontrolled practice, it affects everything on

The Dark Mountain Project: or how literature can confront ecocide

One impulse from a vernal wood May teach you more of man, Of moral evil and of good, Than all the sages can. Wordsworth, “The Tables Turned” (fragment) Words are elementary. The only reason we can

Are there no women in the history of philosophy?

Do only men philosophize? This could sound like a silly question, but if we quickly review the names of philosophers, from Aristotle to Slavoj Žižek, it would appear to be an exercise that is

Things that are about to disappear: photography as environmental conservation

Cristina Mittermeier is the founder of the International League of Conservationist Photography (iLCP), and is at the front of a modern movement to use photography with environmental purposes. Her work

Architecture And Music; An Affair That Acts On The Matter

A composition is like a house you can walk around in. — John Cage Perhaps music, more than the art of sound, is the art of time. That’s why its communion with space, and architecture, is so often so

Psycho-geography (On The Ritual Casting of a City)

Mrs. Dalloway walked down the streets of London guided by an “internal tide” that made her stop somewhere, enter a store, turn at the corner and continue her journey, as if she were adrift. La dérive

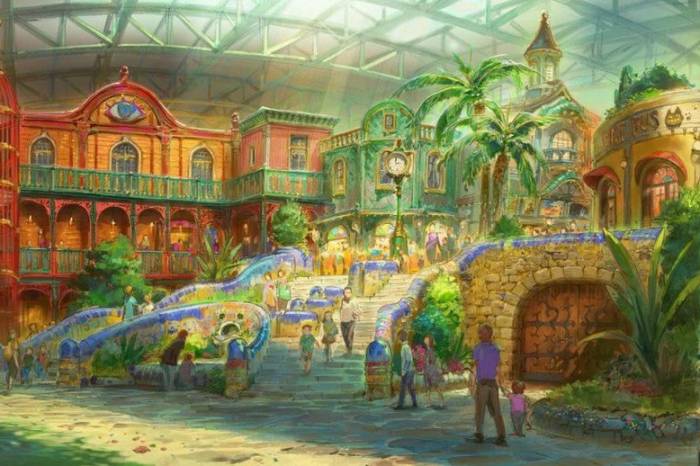

A Theme Park Inspired by Hayao Miyazaki is About to Open …

One of animation’s most spectacular exponents, Hayao Miyazaki, is the artist who transformed the direction of traditional animation forever.