Burning Man: An Explosion of Creative Rebellion in the Desert

Each year thousands of artists and onlookers come together and participate in an unparalleled creative community.

In Black Rock City, a fictional, improvised city –– which is every year dismantled by fire –– located in the Nevada desert during seven days a year, people have been meeting for over 13 years now to experience what the event’s organisers call an “experimental community of self-expression and self-sufficiency”. This is importance: they define themselves as a community. So, what does this community actually consist of?

The foundations of this idea can be traced back to San Francisco in 1986, where an idea, similar to the one we now know, emerged. Larry Harvey, founder of Burning Man, conceptualised it as a Dadaist festival where artists could meet to show their work in a determined period of time and space, without the usual practices of pre-established social reality — without financial exchange, for example. It is an artistic fair, itinerant in time (each year) and in space (because, who can be sure they set foot in the same desert twice?).

The idea of “leave no trace” is central to the festival’s ideological context, since the city’s eccentric buildings are ephemeral; by burning these constructions at the end, everything remains as if nothing had happened in the first place. People draw and erase a world that exists only while it is inhabited, as a world of dreams. There is an idea of cleanliness, in the ritualistic sense, in relation to the respect held for the place that presents them this opportunity. For seven days a community is set up where the surroundings appear to be taken from a Dali painting, or from a shared lucid dream. A utopia where we can influence reality from the logic of a dream is effectively achieved in Burning Man.

Art cars, bionic dance, earth harps, sonorous buildings, allegorical cars, and many, many people. Last year, 53 thousand people assisted the ritual. The levels of the artistic displays are extraordinary and many of them attend as scholarship recipients on behalf of the organisers; other artists, of course, attend for the brilliant opportunity to show their work. It is also a manner of questioning the use of space, testing other communication practices, generating other types of interaction in a conscious relation to the medium. Evidently, nobody litters the place, and whatever people take is shared spontaneously, since the nearest gas station is 40 kilometres away.

Lastly, the event is a phenomenological reduction of reality: during seven days, the quotidian is suspended and a utopia of well-organised artists is entered. A strange thing. Some call it magic.

The atmosphere experienced there is that of a carnival, a ritual, a community. People take the necessary provisions for the experience; the attendees are able to enter another interactive model. On Saturday, the last day of the festival and Labour Day, they burn an enormous sculpture of a Man, where all the written or drawn records made by the assisting crowds are kept. Tears are shed. They enjoy their own practices and rituals. They leave. The desert remains unharmed. Molly Stevenson, a participant and chronicler in the last edition of Burning Man, says: “Your mind is your own drug. Bring enough food, water and shelter, because the new planet is tough, and you will not find anything to buy. You are here to celebrate: on Saturday we will burn the Man”.

Image credits:

1. Oliver Fluck

2. Bill Hornstein

3. Unknown

4. Jim Urquhart

Related Articles

When ancient rituals became religion

The emergence of religions irreversibly changed the history of humanity. It’s therefore essential to ask when and how did ancient peoples’ rituals become organized systems of thought, each with their

Larung Gar, the valley that is home to thousands of Buddhist monks

If we think about the monastic life it is very probable that we think about solitude, seclusion, silence and a few other qualities whose common denominator is the appropriate isolation for mediation

Dialogue with the Dalai Lama on science and spirituality

The Dalai Lama has been interested in science since he was a child. Over the years he’s visited many laboratories and has attended conferences that discuss consciousness from the scientific point of

A New Year's resolution for the earth

Worrisome quantities of waste are generated by human populations. Especially in cities, these have reached unprecedented and alarming levels. A largely uncontrolled practice, it affects everything on

The Dark Mountain Project: or how literature can confront ecocide

One impulse from a vernal wood May teach you more of man, Of moral evil and of good, Than all the sages can. Wordsworth, “The Tables Turned” (fragment) Words are elementary. The only reason we can

Are there no women in the history of philosophy?

Do only men philosophize? This could sound like a silly question, but if we quickly review the names of philosophers, from Aristotle to Slavoj Žižek, it would appear to be an exercise that is

Things that are about to disappear: photography as environmental conservation

Cristina Mittermeier is the founder of the International League of Conservationist Photography (iLCP), and is at the front of a modern movement to use photography with environmental purposes. Her work

Architecture And Music; An Affair That Acts On The Matter

A composition is like a house you can walk around in. — John Cage Perhaps music, more than the art of sound, is the art of time. That’s why its communion with space, and architecture, is so often so

Psycho-geography (On The Ritual Casting of a City)

Mrs. Dalloway walked down the streets of London guided by an “internal tide” that made her stop somewhere, enter a store, turn at the corner and continue her journey, as if she were adrift. La dérive

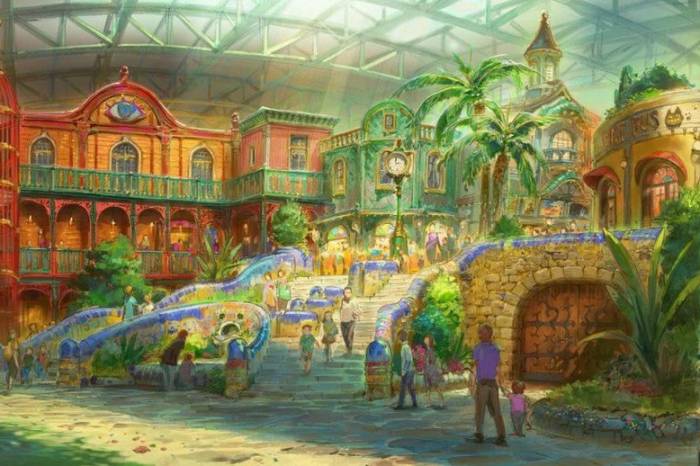

A Theme Park Inspired by Hayao Miyazaki is About to Open …

One of animation’s most spectacular exponents, Hayao Miyazaki, is the artist who transformed the direction of traditional animation forever.