On the Relationship Between Edward Hopper's Paintings and Cinema

Hopper’s work and cinema have exercised a mutual influence over each other as part of a beautiful dialog.

Edward Hopper (1882-1967) was a celebrated US painter who had a notable influence on cinema, both in form and depth. This is mainly due to his unique way of using light, but also in his compositions, the arrangement he gives to objects and people in their spaces, the attitudes of the characters and the peculiar use of color.

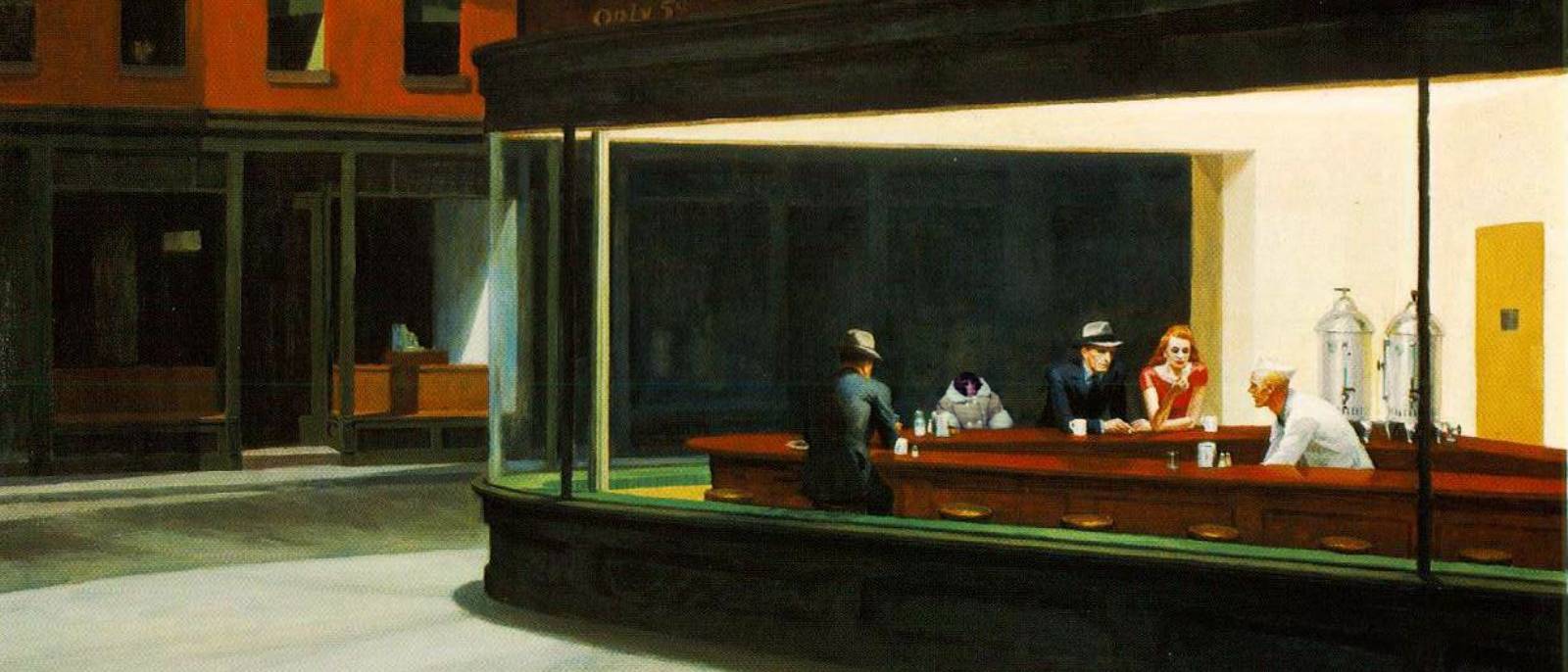

It is worth noting that the relationship between Hopper and cinema is symbiotic and manifests a mutual and not a one-way influence. In fact it would appear that the artist’s style is made of celluloid. At one point his wife Josephine revealed that Hopper often went to the cinema alone, at night, in search of inspiration. It is well known that his famous painting Nighthawks (1942) was inspired by a Hemingway story, and it is no coincidence that the later film version of The Killers (Robert Siodmark, 1946), which would have a huge influence on cine noir, uses that painting as a starting point.

Woman as a metaphor for alienation

Somnambulant, diaphanous women with gazes that transcend their respective physical spaces parade through several of Hopper’s works. They appear to be looking at something or someone but are probably directing their gaze at nothing, witnesses of what could be all that exists, suggesting a calm disconnection from reality or perhaps alluding to the post-war evil; that ambiguity in its meaning furnishes the painter with much force.

In a documentary by the filmmaker Ed Lachman he talks about this element in Hopper’s work, and which would later have an impact on cinema: “the painter uses women as a feeling of the alienation from the world in which they live.” Women in this case are a vehicle through which Hopper channels his own moods. The cinema of the second half of the 20th century was fertile ground for this kind of character in cinema, an exemplary version of which is the women in several films by Antonioni (the great poetic film director of alienation) played by his wife and muse, Monica Vitti, such as in Red Desert (Antonioni, 1972), in which she played Giuliana, a bourgeois mother on the verge of hysteria, in industrial landscapes in intense colors that could have dripped from the canvasses of Hopper.

Empty spaces

That spatial emptiness that could belong to purgatory connects Hopper with Giorgio de Chirico, more than with his great influences such as Rembrandt and Degas. Hopper developed this aspect thematically, at the gas stations on the highway or empty train stations, a feature that appears to have influenced Wim Wenders. And the German director’s fascination for the American dream, or for that dark side that hides behind it, translates into a fundamental perspective for understanding the painter. Paris, Texas (Wenders, 1984) is a masterpiece in this sense and appears to have come from a Hopper painting. Robby Müller’s striking photography completes the spell, with saturated colors that pay homage to the master. From the beginning, in Wenders’ early shorts, where there are no characters and only desolate places in fixed shots, that influence was also apparent.

Solitude is intense in Hopper’s paintings that use American diners as a setting. They are places that feel empty even though there are people in them: the diners only see the coffee in front of them and the lack of communication permeates everything, suffocating any possibility of socializing.

Windows and houses

Tall buildings that we see from ground level with open windows, through which we see people looking out, with inconsolable expressions. There are also paintings that depict apartments painted from the inside, making it appear that two separate paintings are part of the same cinematographic scene; we observe lateral, half-scenes, of people looking out and wishing, although without impetus, to fly while bereft of wings.

Alfred Hitchcock hits Hopper’s aim full on in several of his films, but particularly in Rear Window (1955), in which a photojournalist watches his neighbors, with the help of his telephoto lens, from his armchair. Later, De Palma would use the same mechanisms in Body Double (1984), in which the protagonist, using a telescope, is witness to the show that his sensual neighbor puts on. In both movies there is a tense ambiance, as there is in Hopper’s paintings.

The majestic houses on the horizon in Hopper’s paintings represent abandon rather than a cozy home. In particular, the 1925 painting House by the Railroad, is evocative of many films, including Giant (George Stevens, 1956) and Days of Heaven (Terrence Malick, 1978).

In Psycho (1960) that psychoanalytical abandon is taken even further by Hitchcock. The director not only understands the sexual repression or castration expressed in Hopper’s paintings, but he also uses the components to imagine versions in which the characters solve their traumas. Another way of looking at it is that Hitchcock expresses his anxieties, thanks to the feelings inspired by Hopper’s works; Hopper’s art liberates him, provoking sophisticated cinematographic realities loaded with a sexuality that is not fully unleashed.

Whichever way we look at it, the sexual component in Hopper’s paintings is important and it invades the works in different places. Post-coital scenes are evident, with the couple in a cold, disconnected state and separated although together. We can imagine the heated encounter they enjoyed before the work was painted as Hopper once again provokes our imagination. The separation is due to an abnormal situation, or perhaps too normal, perhaps due to a third person that does not appear in the frame, but who is present in the characters’ psyche.

Midday light

Hopper’s work is a clear preamble to American abstract expressionism. The geometrical shadows on the walls at midday and the quality of the light on the objects invoke abstraction. Mark Rothko once said that he never liked diagonal lines in paintings as in their case they were justified by the light that enters into the spaces. The diagonal lines that Rothko refers to are shadows on the wall created from light, but beyond the justification is the texture that Hopper achieves with his technique.

His influence

It would be impossible to imagine the films of directors such as David Lynch, Todd Haynes, Aki Kaurismäki and Terrence Malick without having known the work of Hopper. The brilliant and prolific writer Norman Mailer only directed one film, Tough Guys Don’t Dance (1987), based on his own novel. Although it is not entirely successful, it is a marvelous film for the way in which it executes Hopper’s pictorial ideas.

Edward Hopper completed a painting in 1939 that directly approaches cinema from the canvas. It is titled New York Movie Theater and it is a piece that is directly referenced in films such as Pennies from Heaven (Herbert Ross, 1981) and Far from Heaven (Todd Haynes, 2003). This is the synthesis of the dialog between Hopper and the cinema, two mirrors facing each other, a confrontation that recreates an infinite dialog and which, perhaps for that reason, cannot fail to provoke a certain emptiness.

Related Articles

Pictorial spiritism (a woman's drawings guided by a spirit)

There are numerous examples in the history of self-taught artists which suggest an interrogation of that which we take for granted within the universe of art. Such was the case with figures like

Astounding fairytale illustrations from Japan

Fairy tales tribal stories— are more than childish tales. Such fictions, the characters of which inhabit our earliest memories, aren’t just literary works with an aesthetic and pleasant purpose. They

A cinematic poem and an ode to water: its rhythms, shapes and textures

Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water. - John Keats Without water the equation of life, at least life as we know it, would be impossible. A growing hypothesis holds that water, including the

Watch beauty unfold through science in this "ode to a flower" (video)

The study of the microscopic is one of the richest, most aesthetic methods of understanding the world. Lucky is the scientist who, upon seeing something beautiful, is able to see all of the tiny

To invent those we love or to see them as they are? Love in two of the movies' favorite scenes

So much has been said already, of “love” that it’s difficult to add anything, much less something new. It’s possible, though, perhaps because even if you try to pass through the sieve of all our

This app allows you to find and preserve ancient typographies

Most people, even those who are far removed from the world of design, are familiar with some type of typography and its ability to transform any text, help out dyslexics or stretch an eight page paper

The secrets of the mind-body connection

For decades medical research has recognized the existence of the placebo effect — in which the assumption that a medication will help produces actual physical improvements. In addition to this, a

The sea as infinite laboratory

Much of our thinking on the shape of the world and the universe derives from the way scientists and artists have approached these topics over time. Our fascination with the mysteries of the

Sharing and collaborating - natural movements of the creative being

We might sometimes think that artistic or creative activity is, in essence, individualistic. The Genesis of Judeo-Christian tradition portrays a God whose decision to create the world is as vehement

John Malkovich becomes David Lynch (and other characters)

John Malkovich and David Lynch are, respectively, the actor and film director who’ve implicitly or explicitly addressed the issues of identity and its porous barriers through numerous projects. Now