The Faena Questionnaire Fatboy Slim

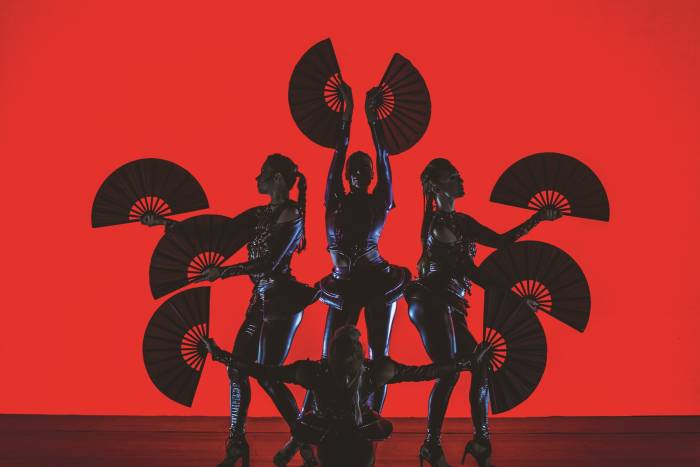

The pioneering British DJ, producer, and musician helped shape the “big beat” genre in the 1990s with energetic live performances and chart-topping hits like Praise You and Right Here, Right Now. With a career spanning over three decades, Fatboy Slim continues to influence global dance culture through his innovative sound and dynamic stage presence.